As published in the "Bahrain Tribune"

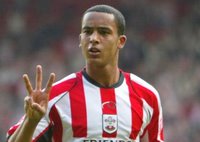

Theo Walcott is a young footballer presently playing for the English club Southampton who is seen as having extraordinary promise. Like the teenage star Wayne Rooney before him Walcott will be a multi millionaire well before he comes of age in two years time. Indeed his financial future will be secure long before he has actually achieved anything in the game as the big clubs (with Arsenal the favourite) compete with one another to sign him. The deal they offer will comprise a huge transfer fee to be paid to Southampton and a salary package for the young man which will ensure that he need never worry about money for the rest of his life (even if his football promise is not a reality when he has to perform at the highest level).

It would be churlish not to wish Theo Walcott well. But I can't help feeling that rewards should somehow be based on performance rather than potential. Remember that Henry Ford once said that you "Can't build a reputation on what you are going to do". Promise has to be fulfilled to be a reality. The same debate could be made around another British sports star the Formula one drive Jensen Button. Button is rich beyond the dreams of avarice and yet these riches have been acquired not because he has been a great driver, but because teams managers think that he might one day be one. Remember that Button, now in his sixth season in Formula one, has yet to win a Grand Prix!

Perhaps I have an over puritanical view that reward in life should be a reflection of achievement. In the world of professional golf, for example, where there certainly have been some examples of players who have got rich on promise rather than success, in the main pros have to work very hard (and be very good) to achieve the mega money being thrown at Walcott or Button. If you look at the prize money at an average PGA event you will see huge prizes for the top five or six finishers. But go down the list and you will notice that even if you make the cut in most events you are not really even guaranteed a prize that will cover your costs. Play badly in any one week and you don't earn anything. The journeymen pros on the big tours in the USA and Europe can make a decent living out of the game, but they usually need one or two top five finishes every year to prosper. The same applies in professional cricket. Play regularly in an international side and you will make good money (and if you are an icon like Tendulkar, Lara, Warne or Flintoff very good money indeed). But your average pro in the County or the State game is likely to be paid very modestly indeed - they really do often play for the love of the game, not its rewards.

It is naïve to think that in the world of today's professional sport money matters are not all pervasive. Too often the actions of sporting administrators, competitors and teams are in stark contrast with the moral principles of the sport. In recent times we have had the illegality of drug abuse, match fixing and cheating in too many case to mention. And we have also seen too often unbecoming on the field of play behaviour by multi-millionaire stars (abuse of opponents, challenges of officials). But when we charge these miscreants with bringing their sports into disrepute (which they do) should we not also be looking at the actions of those who allow conditions to be created within whom these abuses can occur? Many sports have created reward systems which involve so much money that, whilst this does not excuse inappropriate behaviour by players, it does explain it.

Rewards should be more closely linked to performance, rather than promise, and the penalties applied to those who break the rules should be more stringent than sometimes they are. And those who administer sport should behave rather better themselves! Then we might have a world in which sports and sportsmen would set a better example to young people than that set by a foul-mouthed millionaire teenage footballer, a perfomance-enhancing drug taking athlete or a cheating cricketer claiming a catch when the ball has grounded.